Wave Polarization: Some Basics

misc-physics In a spatially 3D universe, one encounters two major types of waves: transverse and longitudinal. The waves are categorized into these two groups in response to the question: Does the wave vary parallel or perpendicular to its direction of propagation?

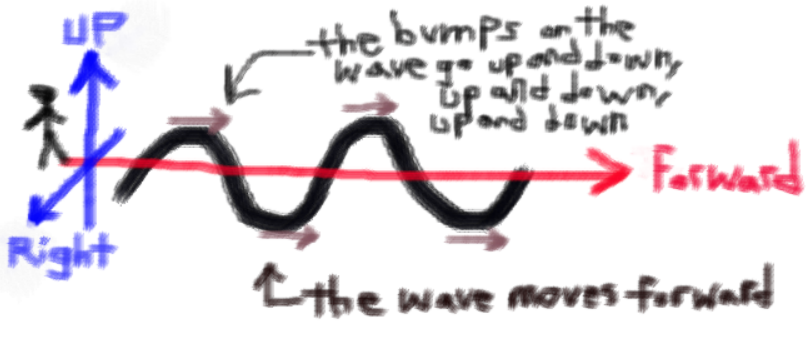

“Transverse” means to crossover something—and in this case, a “transverse wave” means that the wave fluctuates across (“transverse to”) the wave’s direction of propagation. In other words, a transverse wave might also be called an orthogonally-fluctuating wave. Transverse fluctuations take place in the 2D plane perpendicular the the wave’s propagation.

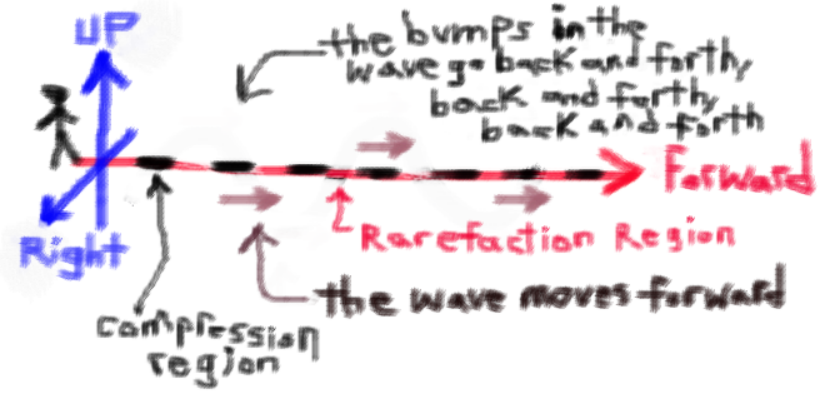

“Longitudinal” means to extend or move collinearly with something instead of across it. So a longitudinal wave is a wave that varies parallel and anti-parallel (i.e., collinearly!) to the wave’s direction of propagation—just compressions and rarefactions along one dimension. If we call transverse waves orthogonally-fluctuating waves, then longitudinal waves might be called collinearly-fluctuating waves.

Polarization

Polarization is a fancy way of saying “orientation,” as in “How are the undulations of the wave oriented?”

For collinearly-fluctuating (“longitudinal”) waves, e.g., acoustic waves, there is only one way to orient the fluctuations. If you guessed collinearly, pat yourself on the back! The fluctuations of longitudinal waves vary in the direction of propagation only, so a longitudinal wave can only exhibit compression and rarefaction patterns along that direction. The compression and rarefaction patterns might differ, but there is only one longitudinal orientation.

Orthogonally-fluctuating (“transverse”) waves, on the other hand, live on a plane, not some skimpy line! Unlike a collinearly-fluctuating wave that wiggles in a one-dimensional subspace, at any one instant, the wiggles of a transverse wave can be decomposed as a sum of two orthogonal orientations (e.g., North-South and East-West, or X and Y). Having two dimensions to wiggle in allows for transverse waves to have an additional degree of freedom: polarization. So, to be clear, from here on out if I refer to the polarization of a wave, I am referring to the polarization of a transverse wave.

Infantilizing Polarization

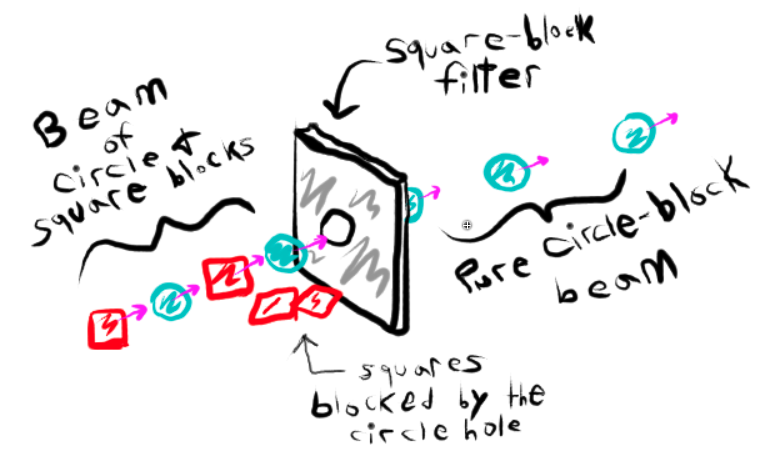

Think about it as a filtering problem: how one would filter a set of randomly-oriented transverse or longitudinal waves in order to end up with an organized subset of those waves? For randomly polarized transverse waves, (e.g., white light) one might use a filter such that only linearly polarized waves of one orientation emerge (e.g., horizontal polarization). But since longitudinal waves have only one sense of orientation, the only way to filter such a wave is to stop it in its tracks!

]

]Polarizing a transverse wave is like a toddler not being able to fit the square peg in the circle hole: the circle hole is the filter, allowing only circles to pass. Not being able to polarize a longitudinal wave is the equivalent of a toddler being able to thread a piece of yarn through any of the holes, independent of shape: the only way to stop the yarn is to plug up all the holes!

Types of Polarization

The most intuitive example of polarization is linear polarization. For example, if a wave is propagating vertically down towards Earth, its plane of polarization at a given point can be described by axes in the North-South and East-West directions. If a wave is polarized North-South, it absolutely does not fluctuate in the East-West direction. Alternatively, the wave can be East-West polarized, or polarized at any angle in the horizontal fluctuation plane.

]

]A wave is said to be circularly polarized when a its amplitude does not change, but its sense of linear polarization does so continuously, tracing out a helix through space—or at a given point, a circle over time. The helix either twists clockwise or counterclockwise. But what does that mean? These terms are ambiguous because they dependent on whether you are watching the wave come towards or away from you. A more robust approach to describing this a wave’s helicity is using handedness. To do so, allow your thumbs to point in the direction of propagation: if the helix twists with your right hand, the wave is right-handed; alternatively, if it twists with your left hand, the wave is left-handed. Pretty simple!

A wave is said to be elliptical polarized if both its amplitude and sense of linear polarization change in time at a given point. Actually, elliptical polarization is the most general type of polarization and, in fact, the formalism for elliptical polarization subsumes linear and circular polarization. Mathematically speaking, for efficiency’s sake, you might just learn elliptical polarization—but physically speaking, it takes quite a bit more effort than linear polarization to understand.

Examples and Stuff!

Electromagnetic waves are transverse waves—the electric and magnetic fields oscillate perpendicularly to its direction of propagation. Pressure waves in a gas are purely compressive—that is, they are collinearly-varying waves, a.k.a. longitudinal waves. However, note that pressure waves in a solid can induce shears and strains, and so have both compressional and transverse components (e.g., seismic waves from Earthquakes).

When considering the polarization of an electromagnetic wave, it is often defined relative to the electric field. However, since the principles and terminology of wave polarization can be applied to any types of transverse waves and given I deal mostly with geomagnetic field measurements, in coming installations of polarization-related topics I will refer to polarization of geomagnetic field variations in terms of the magnetic field (e.g., a vertically-polarized wave in geomagnetic field data refers oscillations in the data that vary only along the vertical axis).

Next in The Wave Polarization Series: